For decades, the conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh in the Caucasus has been a recurrent source of conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan. In the past weeks the conflict has escalated: since the end of September there has been a war.

Under international law, the region of Nagorno-Karabakh and the surrounding provinces belong to Azerbaijan, but have been occupied by Armenia since 1994. The Republic of Arzach, proclaimed in this area and supported by Armenia, is not internationally recognized. Currently, Azerbaijani troops with Turkish political support are advancing and attacking the region including its capital Stepanakert.

According to media reports, attacks on civilians and civilian facilities are lamentable on both sides. Nonetheless, the conflict is receding into the background in European public opinion. The suffering of civil society is hardly reported.

In the context of our Discuss Europe Event on the 17th of November, we also want to give the people in Armenia, Azerbaijan and Nagorno-Karabakh a voice and therefore we have talked to people from the different regions about their current situation.

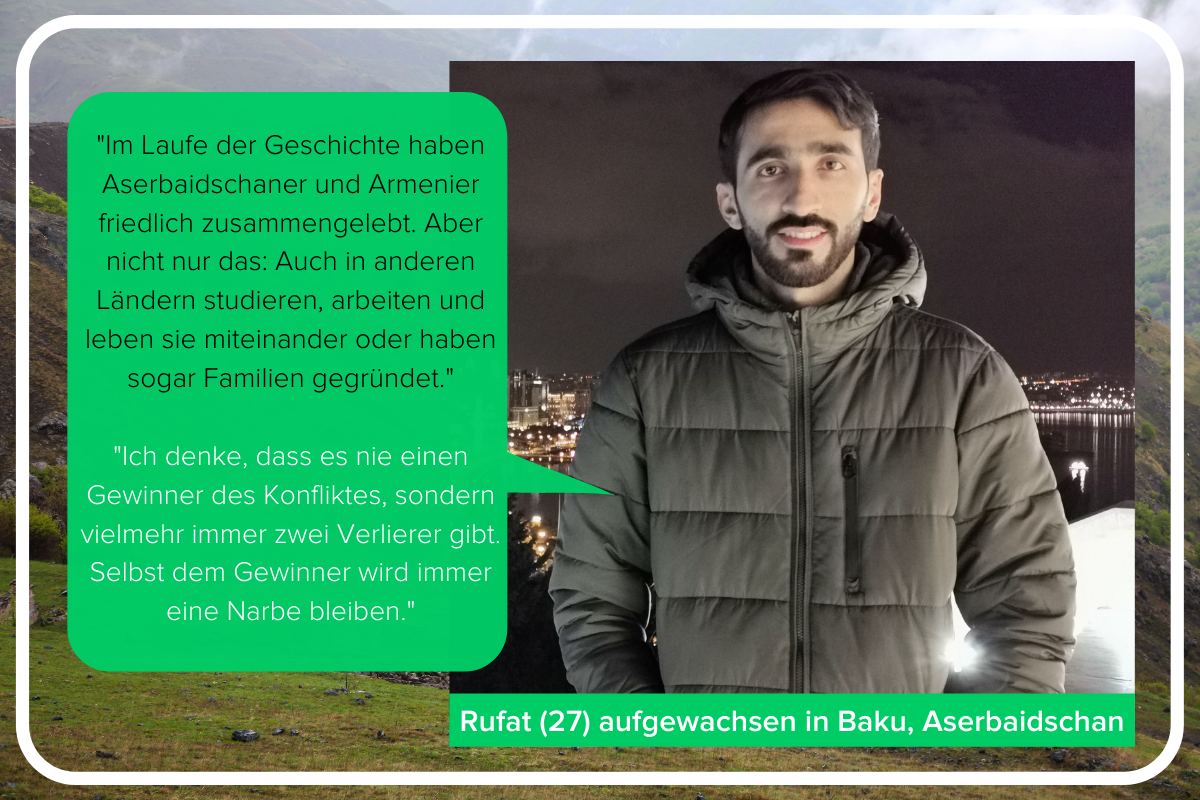

Today’s interview is with Rufat (27) works in Hamburg and did his Masters in European Studies. He grew up in Baku, in Aserbaidschan.

To what extent are you or your family affected by the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict?

Rufat: As an Azerbaijani I have to say that I and my family are also affected by this conflict. My grandmother originally comes from the Karabakh region. During the First War in Nagorno-Karabakh (1991-1994), about one million people were displaced from their homeland – many were dispersed among the different cities of Azerbaijan, often going to Baku (that is where I come from). I remember the stories my parents told me about the hardest time of their lives. Since I was born in 1993 (during the First War in Nagorno-Karabakh), I had a hard childhood, marked by famine and pronounced suffering spread all over the country.

During my school and university career, not only in Baku but also in Flensburg (we were 5 Azerbaijanis), I met again and again with acquaintances who also came from Nagorno-Karabakh and the 7 annexed regions in the surrounding area. The many moments I experienced with them and the memories they shared with me about their motherland played a special role in my life.

How do you deal with the conflict? What do you think about it?

Rufat: Since September 27th (when the Second Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict started) I have been going through the day in a tense way, even though the conflict is far away. In fact, since the cease-fire in 1994 there have been different stages of escalation between Armenia and Azerbaijan and unfortunately, many people have died so far. Unfortunately, there has never been a real de-escalation.

I studied International Relations (Bachelor of Arts) and European Studies (Master of Arts), so not only the war but also many conflicts were part of my academic background. While reading history and researching various conflicts in the world, I came to the conclusion that there is never one winner of a conflict, but rather always two losers. Even the winner will always have a scar.

Nevertheless, history is never free of demons that would quickly sow hatred in people’s minds. This ego has always made people want more. And this is exactly what happened during the first war in Nagorno-Karabakh. Armenia won this war and expelled one million Azerbaijani people from their homeland and then set about declaring this area a „security zone“ for its people. Unlike other conflicts, this case is to be seen as a complete „ethnic cleansing“ of the Azerbaijani people, as their historical traces vis-à-vis were erased from the region, the traces of an entire nation.

Throughout the history Azerbaijanis and Armenians have lived together peacefully. But not only that: also in other countries they study, work and live together or even have founded families together.

During the following 27 years Armenia has tried to eliminate the complete historical memory or culture of memory of Azerbaijan from the region and pretended to be the victim. Certainly, one or more people can lie, but not a million people who have been displaced. It would be like telling that there is not one Syrian refugee in Germany – the Armenians deny, as said, that they have displaced one million Azerbaijanis.

I am thinking at the moment about every person who is fighting in this war and about his family, whether Armenians or Azerbaijani. Throughout the history Azerbaijanis and Armenians have lived together peacefully. But not only that: also

in other countries they study, work and live together or even have founded families together. But to badmouth an entire nation, to call it inhumane or even to wish her death is against all humanity and must be condemned.

Do you have contacts with people in Azerbaijan? Has anything changed since the last outbreak of the conflict?

Rufat: I studied together with two Armenians. Especially with one of them I had a very good, friendly relationship. I also work with two Armenian colleagues at my work in Hamburg.

Usually the first part of the conversation is about the attitude or viewpoint regarding the conflict. In my opinion it is an important key between Azerbaijanis and Armenians to start a conversation in a reasonable way. I wish that there would be a world where people could talk to each other easily and openly.

Do you see possibilities for peaceful conflict resolution? What could this look like?

Rufat: In fact, I even see a solution! There must be a common solution in the sense of both nations. However, under the present circumstances, one cannot simply end the war at once, that is difficult to do – unless one of the two nations would admit defeat. As I said before, the war is a lose-lose situation for both sides.

I would now like to propose my own view of the future of the region and my vision of a dream of future development:

In the global world, borders lose their importance, but trade agreements are of great value. The Caucasus is only a small region consisting of three countries, namely Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan. If these three countries would combine their economic power, they could develop constantly and rapidly. The region forms the link between East and West and can be seen as a trade corner.

Once the war ends and peace finally comes to the countries, a new chapter will be opened for this region. A new chapter without hate and anger, focusing on the prosperity and health of the people. It will be anything but easy, but I firmly believe in it.

What do you hope for from the European Union to solve this conflict?

Rufat: The EU probably has the most experience on this planet in reconciling people. Throughout its history, the European continent has experienced a series of endless wars or confrontations, including two world wars. Today, however, this is a long time ago, there are no conflicts between countries, there are close trade relations and interdependence between countries in times of peace. I could mention several countries as examples.

Azerbaijan and Armenia are both countries that identify with European values and have efforts to move closer to Europe. It is precisely this positive influence that the EU should use in the region.

Azerbaijan and Armenia are both countries that identify with European values and have efforts to move closer to Europe. It is precisely this positive influence that the EU should use in the region and show that the path to economic integration is better than the territorial claims of another country and ethnic-cultural-historical cleansing.

Back to the conflict: The EU can and should also use its positive influence BUT it should not be an arbitrator or only an objective observer from outside in the resolution of the conflict, as it has done since the outbreak of the conflict.

RAFUT’S POLITICAL REMARKS

This is a very important point to consider, because the relationship of the EU member states with Azerbaijan and Armenia is not uniform and mostly one-sided.

Take the example of France: there are more than 1.5 million Armenians who are French citizens and live in France. In this way it is easy for them to intervene directly in or influence the political decision-making process, here also in public media, for example on television, in order to get support.

French President E. Macron has made a strong statement to Azerbaijan since the first day of the conflict, despite the fact that France is a permanent member of the OSCE Minsk Group (created in 1992 by the Ministry for Security and Cooperation) and the mandate actually commits France to full objectivity and neutrality.

Furthermore, there was great pressure from Armenians against French journalists (TF1) after they published an article about an Armenian military attack on civilians in Azerbaijan.

After this pressure, TF1 unfortunately decided to remove this report from its website. Journalist Liseron Boudoul received dozens of offensive messages in the social media after he was on television about the situation in Nagorno-Karabakh. The report showed daily life on the Azerbaijani side of the war front. Shortly after its publication, Boudoul received a whole series of hate mails and insults that lasted for several days.

On the other hand, there are EU member states that have close trade relations with Azerbaijan (Azerbaijan has a significant role in the European energy sector in the field of oil and gas) and also publicly recognize the territorial integrity of Azerbaijan (recognized by the United Nations), such as Italy and Germany.